Bevilacqua: “I’m winning today”

When he was in the lead he became unbeatable. His leads were deadly. He’d dissipate the group, turning it into an untidy swarm and forcing it to get in single line, tongue dangling. With him in front there was not even time to throw a sandwich down. With his unbeatable pace, the Venetian cyclist would display a rare cycling power: he was used to straining and the top gear. His bony and slim legs, made smooth by camphor oil, were like pistons. Speed was his forte and on flat stages he would quickly reach first place. He’d start smoothly, accelerating progressively to then reach a racing speed and running solo. Very few cyclists were able to keep up with him in chasing tests: Coppi, Van Steenbergen and a few more other champions. Toni Bevilacqua that year (1950) had prepared diligently for the Milan-Vicenza, a road race that was valid to award the tri-colour jersey. Toni felt he was in top shape. While training lately he had realised he was on the right track. At the eve of the race he approached Tullio Campagnolo, the hopeful former cyclist who, after quitting professional cycling, had moved to patenting. With a carefree tone and a cunning expression on his face he pronounced the sentence he had long been brooding over, trying to sound as honest as possible: “If you give me 50 thousand lira, I’ll have your gear mounted on my Wilier and will win the race”. In those days the copper plated bikes would come with a Simplex gear imported from France, whose first models, presented in 1938, would promise wonders.

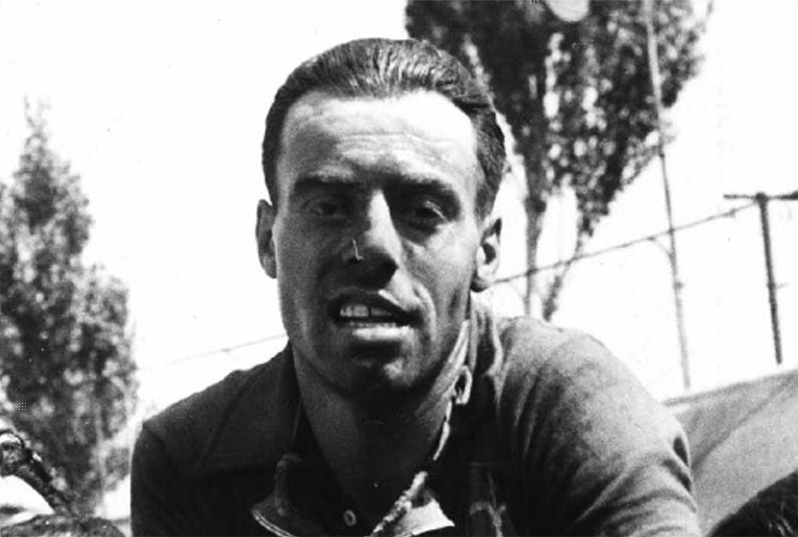

Smiles on Bevilacqua and Cottur’s tired faces,

show that their efforts have not been in vain.

Genova, June 16, 1946

Bevilacqua winner

of the second stage of Giro d’Italia is cheered after the finish.

The small lever secured on the handlepost controlled the mechanism and allowed the rider to move from the first to the third pinion of the freewheel while pedalling. A godsend for athletes, who could choose the best gear ratio based on the type of road. Bevilacqua was fussy. Before the race he’d carefully check the mechanical set and test the pressure of the tyres with his thumb (of the Clement or Gardiol type) depending on the trial. He wanted his tyres fully inflated, close to burst, and would get in a mood if the frame had a single speck of dust on it. “So, Mr. Tullio – pressed Bevilacqua, trying to hide his Venetian sounding “R”, as Campagnolo had not dignified him with an answer yet – are you in? Fifty thousand and I’ll mount your gear: it would be a sure victory”. The builder from Vicenza smiled at him: “Don’t you think you’re going over the top? How can you be so sure you’ll win the Milan-Vicenza against all of your many adversaries?” Toni realised that his proposal had failed to lure the man from Vicenza and his wallet. “We’ll meet in Vicenza” he said aggressively. Campagnolo shrugged. The next day Bevilacqua got up earlier than usual and having already warmed up he went down to the dining room where Cottur and Bepi were waiting for him. He sat at the table and indulged on everything on offer: buttered rice, rare fillet, potatoes as side dish and two slices of tart. He did not decline a full glass of red wine.

He got close to the mechanic and winked: ”I am winning today” he whispered, knowing he had full control over the race. The first few kilometres were ridden at a moderate pace. After all he had eaten, his digestion was long and complex. After passing Bergamo and Brescia, the racers started to work the crank more eagerly. Bevilacqua was in the thick of it and had the head of the race under control. In Verona he shot past as only he knew how. His leg would respond perfectly, his eyes fast and the struggle now a thing of the past. He went over the last few kilometres of the race with his mind, he could see the straight road to the finish line. He decided how and when he’d leave. At the entrance to Vicenza, the group suddenly accelerated. The sprinters gained positions, jostling to get to the first line. Bevilacqua let them pass. Under the banner of the last kilometre, he sprang like a bullet, his speed rising constantly. No one resisted his lethal progression. He kept his word: he crossed the finish line first with his arms up. Beyond the banner his gaze met that of a speechless Tullio. He wore the tri-coloured jersey with pride. The next day the headlines read: “Bevilacqua triumphs at the G.P. Campagnolo with the fabulous Simplex gear”. Bepi kept that page of the gazette for a long time.