A heart of gold

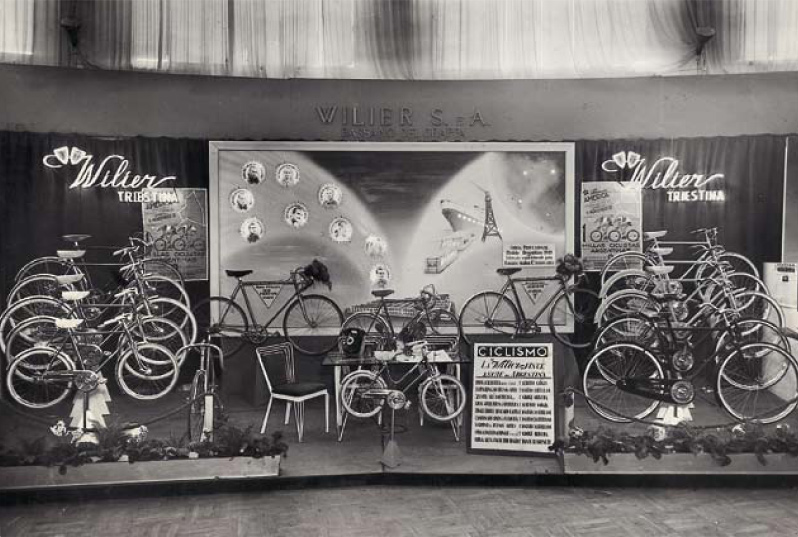

While the slow tolls of the transitus resounded in the leaded sky, the smart grey-haired gentleman walked close to the coffin. His hand gently brushing against the wood and the flowers. For a moment his eyes became moist behind his dark glasses. The friend of many battles, the mate he brought water to, suggested tactics and attacks to and generously pushed along back-breaking slopes, had passed away. He did not want to miss his last appointment with his captain and had endured a 400 kilometre drive on the motorway. Four long hours in the car, driving across the generous Emilia, the hard-working Veneto and the noble Venezia Giulia. Thoughts and memories intertwined during the journey as he went through, like in a movie, the moments that had deeply marked his youth, making him the athlete and man he grew to be. Giordano had passed away and he was there to show him his affection and regard, unchanged after more than sixty years. After professional cycling, Cottur had retired to the margins of the industry and now coached young novice cyclists. He, on the other hand, had stayed in the game, taking a prominent role, leading his pupils to win six world titles and conquer dozens of gold medals. Alfredo Martini left the incense-scented church. He gazed at the clouds and took a deep breath, smelling the salt in the air. The hearse with the wreaths moved slowly. Someone coughing distracted him from his sorrow thoughts. People around him were inspecting him respectfully. He responded to hundreds of people greeting him with his usual friendliness, his Florentine expressions and his clear words. In the meanwhile Giordano was leaving forever. His emotions did not take over although his heart was pounding. He got in his car, ready to drive the 400 kilometres back home, sure he had done the right thing. Trieste, Barcola, Monfalcone. On the background was the huge Redipuglia ossuary with its steep steps. The castle of S. Giorgio di Nogaro followed by those of S. Donà, Noventa, Quarto d’Altino. Mestre bypass and then Venice wrapped in fog. Padua, Rovigo, Ferrara, Bologna. His car passed them quickly. The Apennines are announced by the Basilica of Saint Luke; Sasso Marconi, Pian del Voglio, Mugello and finally Florence. Half of the Giro d’Italia and a tons of memories. Alfredo Martini is always smart, courteous and attentive. A man of rare intelligence, as he was when running, reading and interpreting races like only a few can. Caught in the grips among Coppi, Bartali and Magni, who he recognised as superior, he knew how to gain the limelight with his perseverance and ability to bite the bullet, suffer and never give up. Time might have aged his face but his spirit is always the same. Where his legs and muscles could not reach, his brain would. He was an important racer for Wilier Triestina in 1948 and 1949, asked by Zandonà to wear the illustrious jersey together with the other terrible Tuscan cyclists, Magni and the Maggini brothers he used to train with daily for kilometres, sharing unspeakable efforts. At the start of the season they would leave Florence by bike, climb the hostile mountain and dive off into the plain to reach Bassano where Giordano Cottur would be waiting for them. The first training sessions, at the foot of Mount Grappa, aimed to improve and strengthen teamwork, which never flawed, not even after decades. Martini never fired up, keeping a low profile, like the wise man he is. “I have been an average racer – he says about himself – not winning much. But I would reach the first places also in difficult races 300 kilometres long, where champions like Bartali and Coppi would dominate”. The third place at the famous Cuneo-Pinerolo was extraordinary: It was the 10 June 1949. Leoni had departed with the pink jersey. Coppi was seconds away with 43”. Gino, third, reached 10’11”, Cottur was fifth at 15’02”, Martini ninth at 20’26”. Heavy black clouds suggested cold, water, pain and fatigue. Coppi sprinted immediately and one after the other accomplished the Col de Vars, the Col d’Izoard and the Col de Montgenèvre. Gino, the iron man, could not keep up with him. The champion’s advantage grew visibly. A legendary stage, which made cycling history. Coppi covered the 254 kilometres that separate Cuneo from Pinerolo in 9 hours 19’55”. Bartali, right behind him, suffered a delay of 11’52”. Martini reached the finish line before Giordano Cottur by a tiny margin, 19’ and 14” after the winner. The classification was revolutionised. Coppi wore the pink jersey while Bartali, second, was at 23’20”. Leoni was third with 25’54”, Cottur forth at 37’33” and Martini sixth at 42’27”. Two stages were left to the end of the race. In the Pinerolo-Turin stage of the next day, a 65 kilometre time trial, Bevilacqua gained the upper hand.

Alfredo Martini

Time trials are strange races. The last spring first, the first last. Sante Carolo, proud of his black jersey and boasted a two hour lead over Malabrocca, could pedal safely, dreaming of being the first in the class rather than the last. His kindly supporters clapped for him the whole time. Very emotional. Corrieri won the Turin-Milan. Cottur overtook Leoni in the classification and reaches the lowest step of the podium. Alfredo Martini had special memories about the Cuneo-Pinerolo, which crowned him as a champion. “An average racer – as he wrongly continues to consider himself – standing right behind the true champions”. “In the forties – he reveals – I went a long way with Gino. I remember him along the ramps of the Abetone and on the Barilozzo. He used to pedal with extraordinary power. I am sure that if it had not been for the War, Gino would have won five tours. He really was made of iron; his resistance was fantastic. I often trained with him. To prepare for the Milan-Sanremo we pedalled for 250 kilometres straight. We’d leave from his house and ride to Arezzo, passing by Monte S. Savino. On the way back, in Siena, I’d join his wheel cause I was exhausted. The kilometres were never enough for him. I’d wear out as I did not share Gino’s class and resistance. We’d only stop to fill up the water bottles. On the saddle from morning to evening, with sandwiches appeasing our hunger. He was very diligent and until he was 30 he’d go to bed at 9 sharp every night. He later started smoking and would stay up until midnight but he could afford to do it given his physique”. An all round racer, Alfredo Martini scored a dozen victories and many achievements. In 1950, having left Wilier and having moved to Taurea, he wore the pink jersey for one day. That year he scored the best result in the pink race: absolute third. He ended his career next to Fiorenzo Magni, in the Nivea Fuchs, the captain who he had served with dedication and loyalty also at Wilier Triestina.